A James Bond Day Plea to Hollywood: 007 Doesn’t Need a Radical Makeover

Originally published at NYDailyNews.com

Today is James Bond Day, marking 60 years since the world premiere of “Dr. No” and celebrating the longest-running film franchise in history.

In 2022, Bond is caught up in changing times. Amidst calls to make Bond female or gay, questions pertaining to “evolution” and “progress” are being asked of the entire franchise. Is Bond himself, the macho (or misogynistic) British secret agent, outdated?

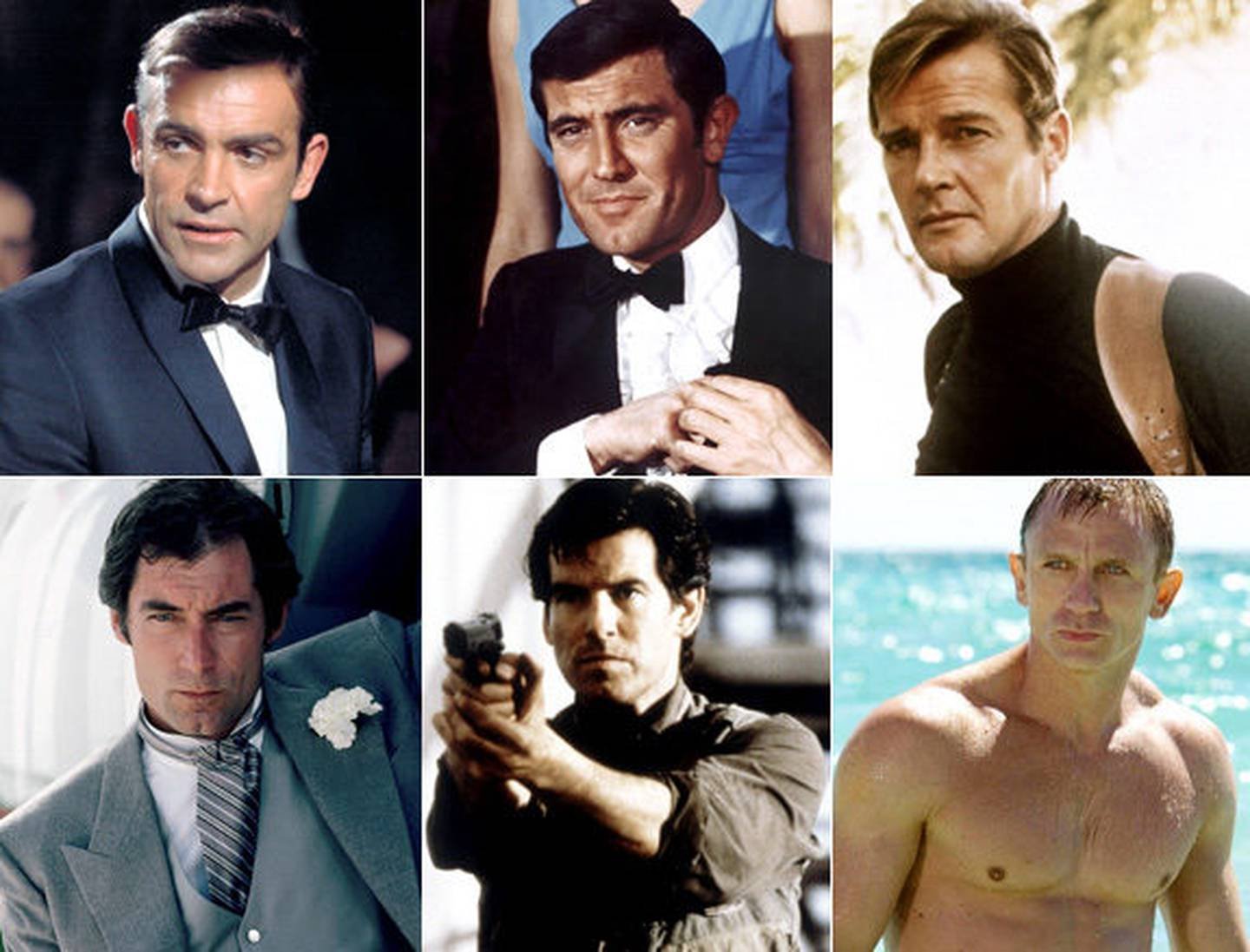

As producers of the Bond franchise Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson search for a new 007 to replace Daniel Craig, who’s the seventh actor to play the part (fifth if you don’t count one-offs David Niven and George Lazenby), they have hinted at updating the character. In Broccoli’s words: “Bond is evolving just as men are evolving.”

Tread carefully. There is no need to change the character for change’s sake. The passage of time alone does not necessarily equate to “progress.”

Of course, it surely can: Bond has already evolved plenty since 1962. He no longer slaps women on the behind (see: 1964′s “Goldfinger”). That’s a good thing. He no longer grooms and dresses himself like a stereotypically Japanese man (see: 1967′s “You Only Live Twice”). That’s also a good thing.

Exploring Bond’s emotional depths is fair game, despite the skepticism of some traditionalists. Ian Fleming’s literary character often questioned his place in the world (read: 1955′s “Moonraker”). Films like 2012′s “Skyfall” successfully raised Bond’s creative ceiling by digging deeper.

There is also no reason why a future Bond installment can’t be directed by a female director, as “Skyfall” director Sam Mendes recently proposed. A woman’s directorial touch could reimagine, complicate and elevate the franchise in new ways, à la Patty Jenkins with the 2017 rendition of “Wonder Woman.”

But evolution should not come at the expense of the Bond character himself. That character is the backbone of the entire franchise—the foundation upon which its success firmly rests. Radically alter the character, and the foundation may loosen to a point of no return.

When 2017′s “The Last Jedi” subverted expectations of Luke Skywalker, the character wasn’t elevated; he just came across as a curmudgeonly old man. The eternal optimist from the original “Star Wars” trilogy was gone, and so too was his broad-based appeal.

Retaining key elements of Fleming’s Bond has served the film franchise extremely well for decades. At heart, he is “ironical, brutal and cold” (read: 1953′s “Casino Royale”). Bond is a rascal, a womanizer and an indulger in life’s finer things. That may not make him virtuous, but it does make him a compelling character.

The irony, brutality and coldness resonate with audiences old and new. After all, the Bond franchise has grossed more than $20 billion over the last six decades, while Fleming’s novels have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide.

Bond is also beloved by millions of women, who have seen strong, independent “Bond girls” dating back to the 1960s (my personal favorite is Fiona Volpe). From the womanizing to the fighting and his saving of the world, Bond keeps people coming back to the theaters—even in a pandemic.

Why fix what isn’t broken? It’s also fair to ask: Have men really evolved that much since the 1950s and 1960s?

The last time I checked, much of Bond’s initial appeal is still relevant and desirable in today’s society. Competence is good. Strength is good. So are bravery and courage. Charm and charisma matter too, as “Top Gun: Maverick” proved yet again.

Looking back now, Sean Connery’s confidence radiates just as much now as it did in the early 1960s.

Sure, men have changed in some ways. Today, they are more likely to discuss mental health or share their emotions, and that emotional openness can be beneficial—but not in all cases. Sometimes, an economy of words plays better than spilling them all out. Especially for spies.

While celebrating the modern man’s heightened emotional vulnerability, let’s not pretend that vulnerability is always good—or even most of the time. It is case-specific. Traditional masculinity can still be a force for goodness and greatness.

Updating Bond works best when the work is put in—when attention to detail is paramount, not identity politics. Bond’s producers should approach the character’s next transformation like Craig tackled his own stunts and portrayed the emotional range of a scarred anti-hero—adding to that character, rather than changing him. Being lazy or scoring cheap political points does nothing to move the ball forward.

Fortunately, the franchise remains in good hands, with early signs pointing to the producers taking their responsibilities seriously. As they showed by choosing Craig in 2005, strategic change today can preserve the character tomorrow—and 60 years from now.

But change for change’s sake will dig Bond’s grave much sooner than expected. There is always time for 007 to die.